By Fasuyi Tolulope Samuel

There was a time when Nigerian monarchs wielded supreme authority. In the pre-colonial era, kings such as the Alaafin of Oyo and the Emir of Kano held power and influence that stretched far beyond the walls of their palaces.

They were not just rulers but semi-divine figures whose every command was law. However, the Nigeria of today paints a starkly different picture, where monarchs no longer enjoy the absolute reverence or control they once commanded.

From thrones adorned with authority, we now see monarchs relegated to ceremonial figures, sometimes even objects of mockery or humiliation.

The removal of the former Emir of Kano, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, by government decree in 2020 shocked many Nigerians, highlighting the fragile nature of contemporary monarchies. His removal, done with political overtones, signaled a significant shift in how modern Nigeria views its monarchs.

In the past, such an action would have been unthinkable. Monarchs were untouchable—legends in their own right, answerable only to their people and the gods. Today, however, kings can be deposed with a single political decree.

Equally, during the 2020 #EndSARS protests, the humiliation of the Oba of Lagos, when his royal staff was stolen by thugs, marked a moment of reckoning. The royal staff, once a sacred symbol of authority, was reduced to an item of ridicule. This would have been unimaginable in the days of Oba Ovonramwen or any of his predecessors, whose authority was sacrosanct.

So, what changed?

The colonization of Nigeria altered the power structures of these traditional kingdoms. British colonizers introduced indirect rule, where monarchs became mere puppets, answerable to the colonial administration.

Though they retained a semblance of power, it was largely symbolic. Post-independence Nigeria has further stripped monarchs of their political roles.

Today, Nigeria’s governance is largely secular, with monarchs serving in advisory capacities at best. While they may still command respect within their communities, their influence rarely extends into the political domain.

Moreover, the advent of modern democratic structures has reduced the significance of traditional rulership. Political leaders, elected by the people, now hold real power. In many ways, monarchs have become relics of the past, holding onto traditions that no longer have the same societal weight.

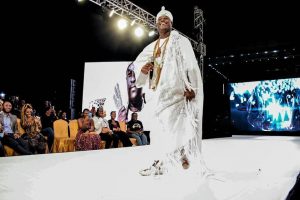

However, some monarchs have embraced their changing roles, transitioning into cultural ambassadors. The Ooni of Ife’s appearance on a fashion runway, promoting African fabrics, is an example of this. His actions, though unconventional for a king, symbolize the new reality for Nigeria’s monarchs. They now play a cultural rather than political role—custodians of tradition rather than governors.

While these shifts reflect the dynamics of a modern society, one cannot help but wonder if Nigerian monarchs have been stripped of too much.

Are we witnessing the end of an era, where kings are reduced to mere figureheads with no real power or significance? Only time will tell. For now, the once powerful thrones of Nigeria are indeed shadows of their former selves.